When considering whether our first responders are properly equipped for the hundreds of thousands of emergencies they respond to each day, we tend to talk a lot about the physical equipment. Do our officers have enough body armor and tools in their belts? Are their vehicles equipped with the right laptops and radios?

These are important questions to ask, but physical gear is only half the battle. What we don’t realize is that our first responders enter dangerous situations every day without the most important piece of equipment they can possibly possess: information.

According to the FBI’s latest report, 9 out of every 100 sworn officers were assaulted in the line of duty in 2014. One-third of those assaults occurred during disturbance calls, which can range from a noise complaint to domestic violence.

While officers respond to a variety of disturbances each year, they typically enter each of these situations blindly and without the information necessary to distinguish if the call has the potential to turn violent. Providing this information before an officer reaches a scene is not just a valuable tool, but arguably the duty of a modern dispatch system.

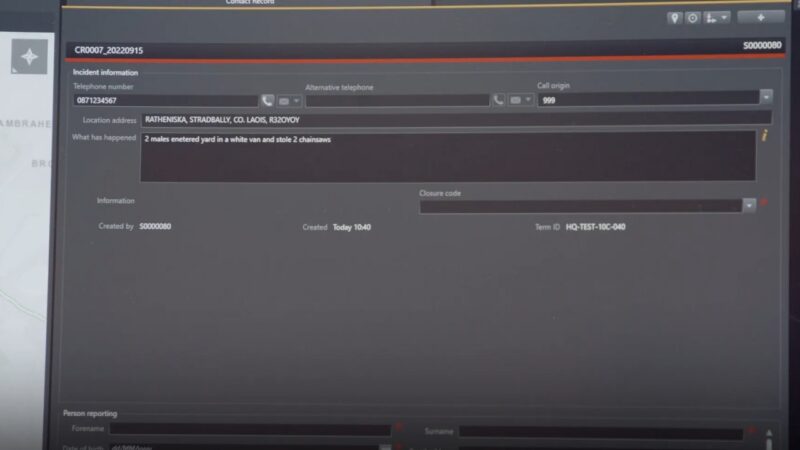

But where does this data come from? Should we expect a computer-aided dispatch (CAD) system to have the relevant backing data to provide officers with key intelligence in the field? Not traditionally. The nature of emergency call data allows current CAD systems to identify repeat callers and requests to the same locations.

However, these callers are often victims or bystanders, and the locations aren’t always the scene of the crime itself. Anything more about the incident is a secondary priority for dispatchers, who are far more concerned with managing a swift response rather than taking down detailed information about a potential perpetrator.

To address these gaps, improving the funding for emergency communication systems is essential, ensuring they are equipped with the latest technology and resources.

Alternatively, in the records management system (RMS), all of this and more is collected in a structured, verified way. Key data like phone numbers, home addresses, relationships, and even social media is entered into a police report well after the dispatcher pulls the reporting number and closes the CAD incident.

Reports can also encompass multiple people and locations associated with the same event and contain the official offense or incident charge filed. Most importantly, the responding officers input this information carefully and thoroughly, knowing it often has to accompany a suspect’s legal record.

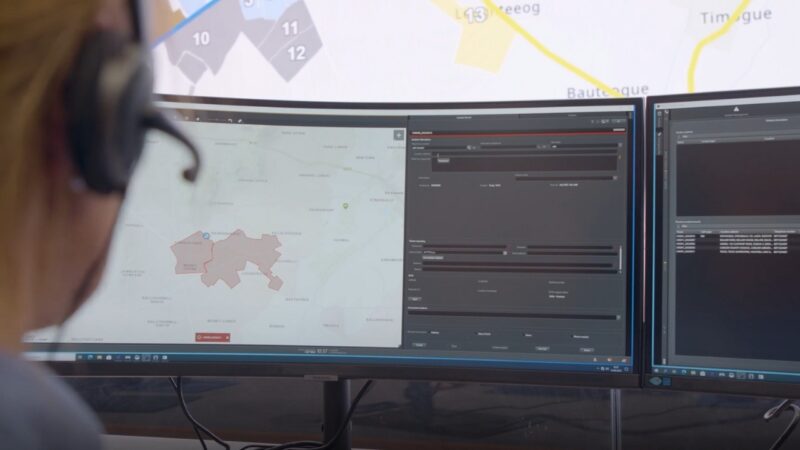

At every stage of an emergency, CAD systems should be able to benefit from these kinds of details. For example, when an officer is en route to an incident at a specific location, the dispatcher can immediately alert the responder if the location is a violent offender’s home address.

Or, using the phone number that called 9-1-1, the dispatcher can instantly identify that the caller was previously a victim of domestic violence, and cue the responder to gather pertinent physical and behavioral traits about the suspect of the prior case.

Modern software advances have taught us that an open, shared connection between CAD and RMS systems is more than possible. A department would never allow their responders to approach a potentially dangerous scene without body armor or a radio. When will we be ready to add crime data — and the software that collects it — to the list of necessary equipment? Isn’t it time for your software to meet that standard?